Douglas Hansen-Luke, Executive Chairman of Future Planet Capital & Rosamund de Sybel, political and economic analyst, writer and consultant.

The road from laboratory to industry is a time consuming and long one, but the rise of a raft of new University Venture Funds (UVFs) in Britain is helping to transform the innovation landscape. The country is now home to an increasing number of firms committed to turning innovative ideas from academic organisations and associated clusters into world class companies.

Britain's venture capital ecosystem is, in many ways, less mature than its US counterpart. There are numerous technology transfer offices in British universities, allowing ideas to be peer examined, tested and patented. Yet seed funds often lack the capital to follow an investment through the necessary growth period and venture capital funds can be reluctant to invest until an idea has been fairly extensively validated. In short, there is a large capacity for additional private sector investment to support such spin-outs beyond the seed stage, particularly in capital-intensive fields such as biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, and nurture them towards maturity.

Commentators often point to the world's best-selling drug: Humira, the rheumatoid arthritis medicine with annual sales of US$13 billion. It was researched by the UK Medical Research Council but commercialised in the US.

UVFs are increasingly helping to plug these crucial gaps, supporting spin-outs through their growth. They hope to increase both the number of spin-outs achieving commercial success and the pace at which they can develop. Pioneers such as Imperial Innovations, established to commercialise Imperial College London spinouts, have been joined by relative newcomers such as Oxford Sciences Innovation (OSI). The latter launched in 2015 and, by the end of 2016, represented the largest fund of its kind in the world, worth over £500 million. “The US is significantly ahead of us in terms of successful spin-outs from universities," says Jim Wilkinson, CFO of OSI. "But hopefully this approach will redress that.”

Although immature in some ways, the British UVFs have key advantages relative to their US venture counterparts when it comes to investing in university innovation. Chief among them is structure: they generally employ evergreen models rather than closed-ended funds which can force premature exits. Victor Christou, the CEO of Cambridge Innovation Capital (CIC) sums up the comparison. “The US has a hugely sophisticated and mature venture capital industry that has provided a different, but successful, base for supporting entrepreneurial companies there through to maturity. In the UK we do not have such a variety of VC investors. But we have instead seen the emergence of several evergreen funds like CIC.”

Indeed, Gregg Bayes-Brown argues that these structural differences in fact make the UK "the most developed place in the world for university venture funding." The former editor at Global University Venturing magazine, now marketing manager at Oxford University's technology transfer unit (Oxford University Innovation), says: "For university innovation you need funding that has a long-term view and the UK excels in that area."

A recent paper authored by the MD of Technology Transfer at Imperial Innovations suggested that, in their experience, "it may take 8 to 17 years for a university invention to reach trade sale or IPO." Data from Spinout UK has shown that spinout companies that saw a successful exit in 2015 (IPO or trade sale) took, on average, just over ten years to progress from incorporation to exit. A 10-year fund structure does not map easily onto this reality.

At Future Planet we believe that British University Venture Funds represent a major opportunity for long-term investors. Furthermore, we believe that even greater benefits can be achieved by unlocking by connecting the key players in the emerging UK university investment ecosystem with each other, and with their global counterparts.

British spin-outs: a snapshot

Britain has some of the finest research institutions in the world. The UK has more top-10 universities per head of population than any other large country. It has also produced more Nobel prize winners. It is home to five of the world’s top 10 medical research universities, including the long-running number one (Oxford), according to Times Higher Education.

However, the number of companies created to commercialise intellectual property developed at and owned by a university remains fairly low. Only Oxford University has produced more than 50 spin-outs in the past 10 years, according to data from Spinouts UK, which tracks this space and this figures pale in comparison to leading US counterparts.

Types of University Venture Fund

In 2017, Bayes-Brown is set to release his University Venture Fund Benchmarking report, backed by the KAUST Innovation Fund. This paper identifies 187 UVF-linked funds worldwide, with just under US$15 billion worth of UVF funding available. Of these UVF-linked funds, 35 are based in UK and their US$4.96 billion in assets represent almost a third of the total. These include a diverse group: seed, proof of concept, early stage venture funds, patient capital funds focused on universities and venture funds backed by universities and institutional investors.

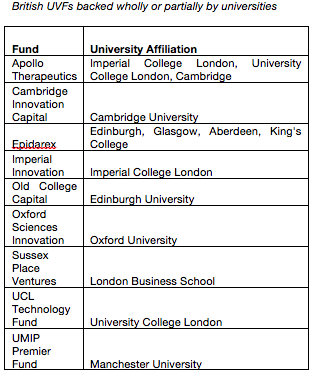

Even the university-owned institutions can be subdivided into those entirely controlled by the university, those partly owned and a third group of multi-university venture funds.

Wholly owned funds include Edinburgh University’s Old College Capital, set up 2011 with support from the University and its Endowment Fund, and Manchester University’s UMIP Premier Fund, which raised £32 million in 2008, making it the largest fund of its kind at the time.

UVFs that are backed by both universities and institutional investors include Imperial Innovations. This fund is backed by heavyweight UK hedge fund Lansdowne Partners and Invesco, as well as the European Investment Fund. Imperial Innovations is both a technology transfer fund for Imperial College London, and a venture company that invests in intellectual property developed at the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, and University College London. It listed in 2006 and since then has invested £160.9 million, while its portfolio of companies has raised investment of over £750 million.

Cambridge Innovation Capital (CIC), which commercialises science and technology from Cambridge University, is also backed by Lansdowne and Invesco. It took on raft of new investors this year, more than doubling its value. Other CIC backers include technology firm ARM, the commercialisation organisation IP Group and the Oman Investment Fund.

IP Group, a pioneer in the sector, was the precursor to the world’s largest UVF, OSI. Fifteen years ago its founder, Dave Norwood, now CEO of OSI, raised £20m investment for a new chemistry research lab for an Oxford academic, receiving in return 50% of the university's stake in chemistry spinouts. This allowed IP Group to invest in Oxford Nanopore, which today is a US$1.5bn company. Today, OSI receives a percentage of the University’s founding equity in every spin out, which has enabled the fund to raise a significant amount of capital.

One of the benefits of UVFs that are backed both by the university and investors, Bayes-Brown points out, is that “they are separate from the university which gives them the flexibility and independence to make investments as they wish. They can also bring outside partners.”

Multi-university funds include the likes of Epidarex and Apollo. Epidarex was created to invest in life sciences in Scotland and across the UK. Its network includes King’s College London, and the universities of Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Aberdeen. When the fund launched in 2013 it attracted £47.5m, backed by Scottish Enterprise and the European Investment Fund, Strathclyde Pension Fund and pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly. Uniquely, four of Epidarex’s investors are top UK research Universities. “Few other universities have invested directly in an early-stage venture fund,” says Epidarex Managing Director Sinclair Dunlop. Apollo, meanwhile, brought the technology transfer offices of Imperial College London, the University of Cambridge and University College London together in partnership with pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Innovation.

Alongside the university stakeholders sit a significant group of UK firms seeking to employ a patient approach to emerging tech spin-outs. The likes of IP Group, Woodford Investment Management and Parkwalk have become cornerstone investors for a number of UK University Venture Funds.